Incident Date:

August 5, 1949

Department:

U.S. Forest Service (MT)

Number of Line-of-Duty Deaths:

13

The Mann Gulch Fire in the Helena National Forest in 1949 remains a tragic and pivotal moment in the history of wildfire management in the United States. On August 4, 1949, fires erupted in the forest after a lightning strike during an evening storm. Three of those fires were quickly found and extinguished—but the other was burning in a remote and rugged area known as Mann Gulch, situated along the Missouri River in Montana. The blaze was initially a relatively small fire, but due to a combination of factors— including hot and dry weather conditions, steep terrain, and unpredictable winds—it rapidly transformed into a deadly inferno that claimed the lives of thirteen smokejumpers.

Morning Vigilance

While the summer of 1949 had not been unusually dry in the Helena Valley, the early days of August were exceptionally hot, with temperatures ranging between 97 and 100 degrees. On the morning after the storm, concerned about holdover fires from the evening before, District Ranger John Jansson asked for a fly over of the area at 6:00 am and additional patrols by Fire Guard James Harrison throughout the day on August 5, starting at 11:00 am.

Reports of Fire

Observer Stermitz Reports

At 8:00 am, Observer Stermitz reported no new fires and all previous fires remained extinguished.

Fire Report from the River

Excursion boat operator Harvey Jensen reported the fire at 11:55 am—but because of phone and radio trouble, the message was not actually relayed until 1:30 pm.

District Flyover

Ranger Jansson landed in Helena at 12:25 pm, seeing smoke.

District Flyover

Still concerned, Ranger Jansson flew over the district at 11:00 am and found no fires.

Report from Lookout

Lookout Don Barker reported that a fire could be seen from Colorado Mountain at 12:18 pm.

Heavy Smoke in the Gulch

Ranger Jansson took off again and flew over the fire site at 12:55 pm, reporting heavy smoke and burning midway up the gulch. He also noted that the upper end of the Mann Gulch drainage would be an ideal site to land a smokejumper crew.

Gathering Crews and Equipment to Fight the Blaze

After hearing Jansson’s report, the Helena dispatcher knew that they would need all the help they could get and went to work recruiting firefighters on the local radio station to join the fight.

After Ranger Jansson landed, he met with Forest Supervisor Moir, who concluded that the soonest resources from town could be put in place would be that evening, leaving the fire plenty of time to grow. Instead, their quickest option to hold the fire would be to mobilize a crew from the United States Forest Service’s newly formed Smokejumper Program. These smokejumpers—a specialized team of highly trained firefighters who parachute into remote wildfire areas— could be deployed in two hours. So Jansson and Moir called upon a crew based in Missoula, Montana, known as the Smokejumpers of the Northern Rockies. Supervisor Moir requested 25 smokejumpers, but there was only space on the aircraft for 16.

The “Size Up”

By 3:00 pm, the fire had grown considerably, and an additional crew of ten with equipment assembled to fight the fire. While Ranger Jansson tried to check in with Fire Guard Harrison, his assistant Hershey gathered more men to join the crew. Jansson found a note on the cabin door that Fire Guard Harrison had gone to the fire. He then sent all 19 crew members to the Mann Gulch/Meriwether Saddle to join the smokejumpers and try to keep the fire from spreading to the ridge.

While the crew headed to join the jumpers, Ranger Jansson went down-river himself to size up the fire. He spotted a fire on the north side of the gulch that was spreading quickly. Just as he noticed the smoke and the heat intensifying, a fire tornado formed and he was forced to run for his life. The heat and hot gas were so intense, he had to hold his breath while he tried to escape, causing him to pass out momentarily.

Ranger Jansson then returned to meet up with Supervisor Moir, who was deploying more resources. He ordered 150 more crew members and two dozers to help fight the fire.

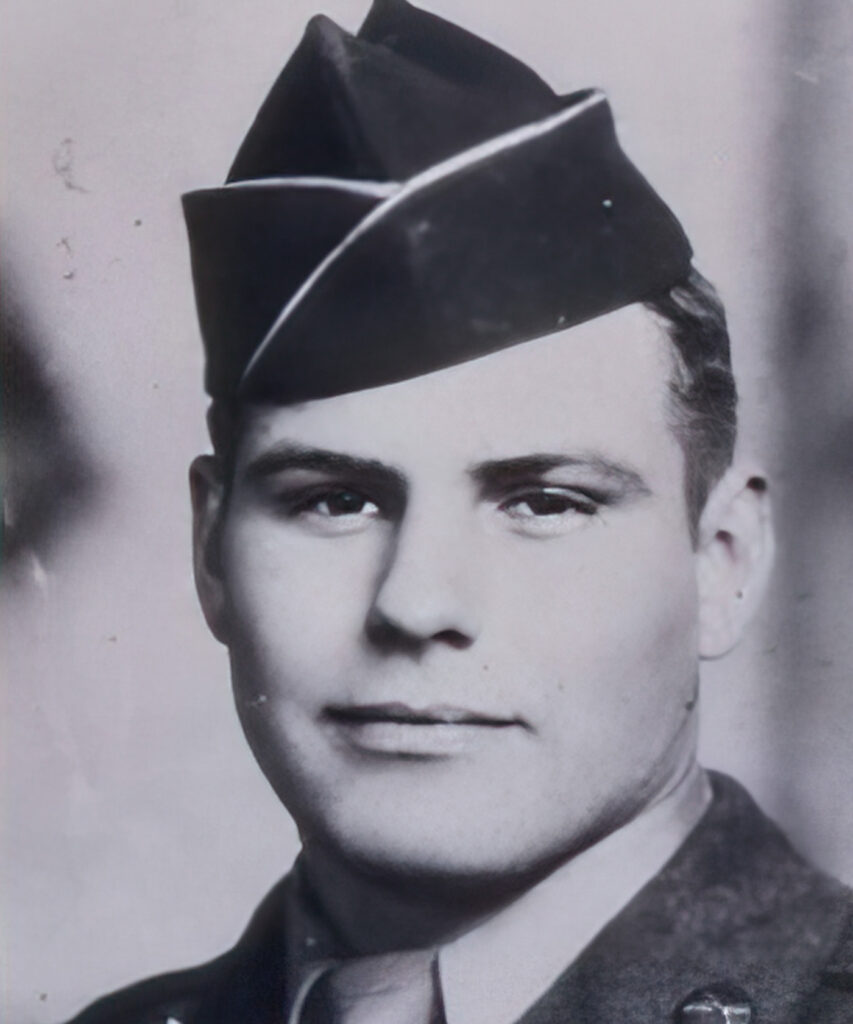

Smokejumpers of the Northern Rockies

Smokejumpers reached the fire at approximately 4:10 pm, discovering a blaze spanning more than 60 acres. Spotter Earl Cooley and Jumper Foreman Wag Dodge chose the jump site at the head of the gulch.

Unsettled air currents compelled their pilot to ascend to a higher altitude than was customary for a jump. The flight became exceptionally turbulent, inducing queasiness among most of the crew members and preventing one individual from making the jump. When the rest of the crew jumped, they scattered widely because of the substantial increase in the jump’s altitude. The parachute for the radio equipment failed to open, sending their only means of communication with the outside world crashing into the side of the hill.

Once on the ground, smokejumpers encountered 100-degree heat with a low humidity of 4%, which created an explosive atmosphere in the canyon.

At 5:00 pm, the crews gathered their gear and ate a quick meal before joining the fight. Foreman Dodge went to meet with Fire Guard Harrison, leaving Squad Leader Bill Hellman in charge of the crew. Their orders were to go toward the river on the north side of the canyon. Harrison and Dodge would meet up with them around 5:40 pm; they planned to extinguish the fire across from them before crossing the canyon.

Smokejumpers of the Northern Rockies

But as they made their way down, Dodge noticed the conditions were changing rapidly and the fire on the opposite side had crossed the canyon. He ordered them back up the canyon. Not too long after that, he had them drop their tools to hasten their quick escape up the rough terrain. The air became sickening as ashes and embers flew around them. After moving about 500 yards back up the canyon, Foreman Dodge knew the fire was going to catch up with them soon. So that evening, Dodge did something that no firefighter had ever done before. He lit what is now known as an escape fire—a controlled burn that results in a safe area, without any fuel left to burn—between himself and the wildfire.

Dodge urged his crew to do the same, but it’s unclear whether it was hard to hear him in the wind and intense conditions, or if they didn’t understand what he was trying to tell them in the chaos. Instead, the crew scattered, with Rumsey and Sallee narrowly escaping the flames as they reached the top of the ridge. Squad Leader Hellman disappeared into the smoke on the left as did Smokejumper Diettert on the right.

After the blow up subsided, they found Squad Leader Hellman and Smokejumper Sylvia. Both were badly burned. Rumsey and Sallee went for help and by 12:30 am a rescue crew with doctors had arrived to help the wounded and search for the missing. Before daybreak, they uncovered the grim reality that the remaining crew members had tragically lost their lives, all situated within a mere 300 feet from one another. And despite the rescuers’ valiant efforts, Squad Leader Hellman and Smokejumper Sylvia died a day later at the Helena hospital.

It is believed that in the blowup stage of the Mann Gulch Fire, the fire spread across 3,000 acres in ten minutes.

Lessons Learned

During the subsequent months, fire scientist Harry Gisborne conducted an inquiry into the fire, formulating hypotheses regarding fire behavior and reshaping the definition of a “blow up.” He too would become a victim, suffering a heart attack while investigating on-site. Fortunately for the wildland firefighting community, he passed a long his findings before his untimely death in November of 1949.

The Mann Gulch Fire played a crucial role in advancing the understanding of fire behavior, safety protocols, and decision-making during wildfire emergencies. It led to increased emphasis on fire behavior research, improved training for firefighters, and the development of more effective strategies for managing wildfires in challenging terrains. Two of the outcomes of this fire included the Ten Standard Firefighting Orders and Eighteen Situations That Shout Watch Out, which were added to the mandatory training needed to work on the fire line. These lessons have since contributed to a safer and more informed approach to wildfire suppression and prevention, and influence firefighting practices and policies to this day.

Influence on Popular Culture

The Mann Gulch Fire of 1949 left a lasting impact on popular culture, primarily through literature and documentaries that recounted the events of the tragedy and its significance in the context of wildfire management and firefighting practices. One of the most notable contributions was Norman Maclean’s book, Young Men and Fire, published in 1992. Maclean, known for his earlier work A River Runs Through It, delved into the Mann Gulch Fire in a deeply researched narrative that explored the lives of the smokejumpers, the circumstances of the fire, and the lessons learned from the disaster. This book, in particular, became a symbol of the fire’s influence on literature and its ability to capture the human side of firefighting and natural disasters.

Documentaries and films have also depicted the Mann Gulch Fire, offering visual representations of the events and their aftermath. A 1952 film, Red Skies of Montana, was loosely based on the Mann Gulch tragedy. Later in 1991, the documentary Fire on the Mountain combined historical footage, interviews with survivors and experts, and a thoughtful examination of the lessons learned.

These visual adaptations have helped bring attention to the tragedy and its role in shaping modern firefighting techniques. While not as pervasive a story as some other historical events, the Mann Gulch Fire has left an indelible mark on popular culture by inspiring artistic works including folk songs and educational works that honor the memory of those who perished.

Lasting Memorials

The Mann Gulch Fire tragedy has been commemorated with several monuments dedicated to the memory of the smokejumpers who lost their lives. One of the most prominent monuments is the Mann Gulch Memorial Site, located near the Missouri River in Helena National Forest, Montana. This site features memorial markers and plaques that honor each of the thirteen smokejumpers who perished in the fire. The site also serves as a place of reflection and education about the dangers of wildfires—and the importance of improved firefighting techniques.

In addition to the Mann Gulch Memorial Site, there is a monument located in the city of Helena, Montana, which serves as a broader tribute to all wildland firefighters who have lost their lives in the line of duty. This monument, known as the Wildland Firefighters Monument, was dedicated in 2000 and includes the names of firefighters from various incidents, including the Mann Gulch Fire.

These monuments stand as enduring reminders of the sacrifices made by firefighters and the ongoing efforts to prevent and manage wildfires more effectively. They also serve as educational tools to raise awareness about the challenges and dangers associated with wildland firefighting.

Miss Montana, the C-47/DC-3 that carried the 16 smokejumpers to the fire, had been restored and on display at the Missoula Museum of Mountain Flying. In 2019, as part of the commemoration of the Allied landing at Normandy—and to pay tribute to numerous crew members who were World War II veterans—the historic aircraft was made airworthy and flew to France for the 75th Anniversary of D-Day.

On August 5, 2019, the aircraft flew over the Mann Gulch once more, dropping wreaths in memory of the heroic smokejumpers and fire guard who lost their lives some seventy years before.

Related:

- Mann Gulch Fire: A Race That Couldn’t Be Won (United States Department of Agriculture - May 1993)

- Mann Gulch Fire | Higgins Ridge (PBS Learning Media for Teachers)

- Mann Gulch...Remembering Those Who Died (U.S. Forest Service - 1997)

- Staff Ride to the Mann Gulch Fire (National Wildfire Coordinating Group)

- Mann Gulch Fire Report

- Mann Gulch revisited: A world turned upside-down (FireRescue1.com)

- Young Men and Fire by Norman MacLean

- Survivor Accounts: Bob Sallee

- Survivor Accounts: Walter Rumsey

- Ten Standard Firefighting Orders

- Eighteen Watch Out Situations

- Meet the 11-year-old carrying on the Mann Gulch smokejumpers' legacy

- The Miss Montana Returns to Mann Gulch to Honor Smokejumpers

- Mann Gulch Photos by the Forest Service Northern Region