Date of death:

August 20-21, 1910

Department:

U.S. Forest Service

Number of Line-of-Duty Deaths:

78

The summer of 1910 would forever be remembered as one of the darkest chapters in America’s firefighting history. What began as an early wildfire season turned into a catastrophe of historic proportions—one that destroyed towns, claimed lives, and reshaped how the nation confronted wildfires.

The Birth of the U.S. Forest Service

Special Agent Examines Forest Conditions

The U.S. Department of Agriculture assigned a special agent to examine forest conditions and report on their health and management needs.

Forest Reserve Act

Division of Forestry Created

This effort expanded into the Division of Forestry, which began to coordinate forest protection and management more systematically.

U.S. Forest Service Created

President Theodore Roosevelt transferred care of the forests to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and appointed Gifford Pinchot to lead the newly established U.S. Forest Service, creating a permanent, professional organization tasked with safeguarding the nation’s forests.

A Season Primed for Disaster

Military Assistance and the Buffalo Soldiers

Photos: U.S. Forest Service

In August 1910, President William Howard Taft deployed 4,000 U.S. Army troops to assist in combating the widespread forest fires in the northern Rockies. Among these were seven companies from the 25th Infantry Regiment, known as the Buffalo Soldiers. They were sent to the towns of Avery and Wallace, in Idaho, where they played a crucial role in evacuating residents and suppressing the advancing flames.

Despite their professionalism and effectiveness, the Buffalo Soldiers faced racial prejudice from some local residents. Nevertheless, the soldiers’ decisive actions—including setting backfires to protect the towns—led to a change in perception, and many residents came to appreciate their efforts.

Their contributions during the 1910 fire exemplify the courage and dedication of the Buffalo Soldiers, who not only served their country but also challenged and overcame the racial prejudices of their time.

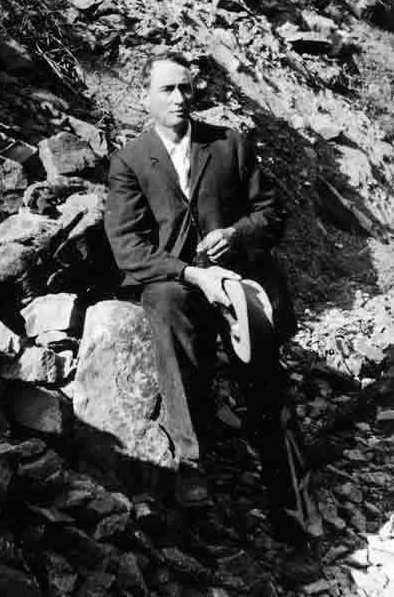

Ed Pulaski’s Fight for Survival

Meanwhile, in the mountains above Warren, Idaho, U.S. Forest Ranger Ed Pulaski led a 43-man crew into the forest as the fire closed in. With no escape route left, he ordered his men into an abandoned mine shaft.

Inside, smoke thickened and panic erupted. One man tried to run for the entrance. Pulaski, knowing escape meant certain death, drew his pistol and declared: “The first man who tries to leave this tunnel I will shoot.”

His uncompromising order kept the men inside and ultimately saved their lives. To hold back the flames and smoke, Pulaski soaked blankets in water pooled on the mine floor and hung them over the entrance. He worked until he collapsed, burned and blinded, overcome by smoke.

By morning, 38 of his men emerged alive. Five never made it into the mine.

Though badly injured, Pulaski continued to serve. He went on to invent a firefighting tool—part axe, part hoe—that still bears his name: the Pulaski. Despite its widespread use, he never profited from the design, and his injuries from the Great Fire haunted him for the rest of his life; he died of a heart attack soon after retiring in 1931.

The mine shaft where he and his crew survived was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, ensuring that the story of their fight for survival would not be forgotten.

A Region in Ashes

The cost of fighting the fire added $1 million to the national debt—a staggering sum for the time.

It remains the second-worst loss of firefighter life in U.S. history, behind only the terrorist attacks of 9/11. To this day, there is no definitive list of who those firefighters were, nor how many succumbed years later to their injuries.

Lasting Legacy

- The U.S. Forest Service’s funding doubled, solidifying its role in protecting national forests.

- The “10:00 am rule” was established—mandating that any new fire should be contained no later than 10:00 am the next day.

- The Weeks Act of 1911 was passed, leading to the creation of six more national forests and the protection of more than 20 million acres.

- Five of the next leaders of the U.S. Forest Service were veterans of the Great Fire, carrying its lessons forward into national wildfire policy.

- The fire cemented the reputation and necessity of professional wildland firefighters, a force that continues to protect America’s forests today.

I want to call your attention to the wonderful work done by the Forest Service in fighting the great fires this year. With very inadequate appropriation made for the Forest Service, nevertheless that service, because of the absolute honesty and efficiency with which it has been conducted, has borne itself so as to make an American proud of having such a body of public servants; and they have shown the same qualities of heroism in battling with the fire, at the peril and sometimes to the loss of their lives, that the firemen of the great cities show in dealing with burning buildings.

Former President Theodore Roosevelt, September 1910